Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorPosts

-

::

The while loop breaks if the std::cin is not in the std::ios::goodbit state. Here are the other state, std::cin could have. I also added a few causes for the specific states:

- std::ios::eofbit

- Reading beyond the last valid character.

- std::ios::failbit

- False formatted reading.

- Reading beyond the last valid character.

- Opening of a file went wrong.

- std::ios::badbit

- Size of the stream buffer cannot be adjusted.

- Code conversion of the stream buffer went wrong.

- A part of the stream threw an exception.

In the concrete example, std::ios::failbit (false formatted reading) is the tyical cause for breaking the while loop.

::First of all, my implementation of virtual overflow member function introduces an indirection:

int_type overflow(int_type c) override { if (myStreamBuffer1->sputc(c) == traits_type::eof() || myStreamBuffer2->sputc(c) == traits_type::eof()) return traits_type::eof(); return c; }

Here is the workflow. One step causes the next step in this sequence:

- log << “1” << ‘\n’;

- sputc() on log

- overflow() on log

- sputc() on the myStreamBuffer1->sputc(c) and myStreamBuffer2->sputc(c)

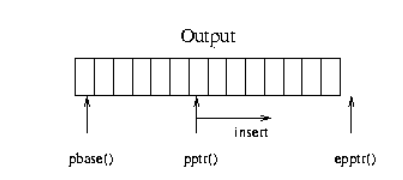

Here is a pictorial description of the output buffer:

- The output buffer is processed by three pointers

- pbase()(put base): the beginning

- pptr() (put pointer): the current position

- epptr() (end put pointer): returns a position after the last character

- When writing to the buffer with the functions sputc() or sputn() the characters are pushed to the buffer until pptr() == epptr()

- When pptr() == epptr() holds, the member function overflow() of the stream buffer is called, so that the characters can be written to the external device

- Afterward, the buffer is empty again and pbase() == pptr() applies

- If you want to explicitly synchronize (flush) the buffer with the external device, the member function sync() is called

- If the stream buffer is degenerated, i.e. consists of only one character, each write to it simultaneously means a call to the member function overflow

::All stream objects have an associated stream buffer. teebuf is derived from std::streambuf. teebuf behaves such as a typical stream buffer with one exception: When characters are written to the associated output sequence via overflow, it puts (sputc) each character to the output sequence and advances to the next position.

Finally, the call std::ostream log(&myTeebuf) creates an output stream using the special stream buffer. The following constructor of std::ostream is called that takes a stream buffer as an argument: explicit ostream (streambuf* sb).

Additionally, I modernized the program from C++98 -> C++11 by replacing virtual with override, and the typedef declaration with the using variant.

#include <fstream> #include <iostream> #include <streambuf> class teebuf: public std::streambuf { public: using traits_type = std::char_traits<char>; using int_type = traits_type::int_type; teebuf(std::streambuf* sb1, std::streambuf* sb2): myStreamBuffer1(sb1),myStreamBuffer2(sb2) {} // overflow will be invoked in case of output // sputc sends the char c to the underlying buffer int_type overflow(int_type c) override { if (myStreamBuffer1->sputc(c) == traits_type::eof() || myStreamBuffer2->sputc(c) == traits_type::eof()) return traits_type::eof(); return c; } private: std::streambuf * myStreamBuffer1; std::streambuf * myStreamBuffer2; }; int main() { std::cout << '\n'; std::ofstream logfile("logfile.txt"); teebuf myTeebuf(std::cout.rdbuf(), logfile.rdbuf()); std::ostream log(&myTeebuf); log << "1" << '\n'; log << "2" << '\n'; log << "3" << '\n'; std::cout << '\n'; }

::Let me quote your two questions and answer them:

- It’s a common technique that a virtual member function of a derived class invokes a virtual member function of the base class with the same name. It’s a kind of a decorator. Y0u have to call the virtual function of the base call fully qualified. When not, you end with a recursion.

- In general, an abstract base class should have no state. On the contrary, if the abstract base class has a static counter, this is a valid use case.

By the way, there is a nicer way in C++17 to initialize a static directly. Use inline:

class Character { public: Character(); virtual ~Character() = 0; virtual void Attack(float applied_damage) const = 0; inline static int characterCount{}; };

::This is undefined behavior: constexpr std::string_view myStringView{“Hello World!”}; You refer to a temporary string literal.

You cannot define a constexpr std::string, but you can use a std::string in a constexpr function.

#include <iostream> #include <string> constexpr int size() { std::string s("adfasdfasdf"); return s.size(); } int main() { std::cout << '\n'; constexpr int len = size(); std::cout << "len: " << len << '\n'; // 11 std::cout << '\n'; }

::First, a short remark. When you use override in a member function declaration, you should not use virtual because override implies virtual. The same rule applies to final.

virtualvoid Print() const override { Person::Print(); //Call base class function to help std::cout << " is a student. GPA: " << gpa << '\n'; }I hope I get you right. To get virtuality or late binding, you need two ingredients: an indirection such as a pointer or a reference and a virtual member function. If one of both is missing, you get early binding:

Person *p1 = new Student("Emmet Brown", "Inventor", 5.0); p1->Non_Virtual_Print(); p1->Print();

The static type of *p1 is Person, but the dynamic type is Student. This means that in p1->Non_Virtual_Print() the static type is used, but in p1->Print() the dynamic type.

Regard hiding.

struct Base { void show(double) {}; }; struct Derived: public Base { void show(int) {} }; int main() { Derived d; d.show(5.5); // calls Derived::show }

When you call d.show(5.5), the name lookup process searches for the first occurrence of the member function show. Consequentially, the lookup process is stopped when Derived is parsed. A better implementation of show in the base class Base is, therefore, not considered.

::This is a typical trap many C++ user fall into. Me included.

You can assign an int to a double, but not a std::vector<int> to a std::vector<double>.

#include <vector> int main() { int i = 5; double d = 5.5; d= i; std::vector<int> myIntVec{1, 2, 3}; std::vector<double> myDoubleVec{1.1, 2.2, 3.3}; myDoubleVec = myIntVec; // ERROR }

In the concrete case, the copy assignment operator on std::vector is called. The types must match exactly match and an int is not a double, and a std::string is not a std::string.

To make this work, a std::vector needs a generic copy assignment operator. I explained this in the following example: https://www.modernescpp.org/topics/example-templateclasstemplatememberfunctions-cpp/.

::Here are the essential C++ rules for default arguments of functions:

- At the point of a function call, the defaults are a union of the defaults provided in all visible declarations for the function.

- A redeclaration cannot introduce a default for an argument for which a default is already visible (even if the value is the same).

#include <iostream> using std::string; // Function prototype void concat(const string& x, const string& y, const string& z); void func(const std::string& x, const std::string& y, const std::string& z) { // Local prototype with default value void concat(const string& x, const string& y, const string& z = "c"); concat("a", "b", "c"); concat("a", "b"); // void concat(const std::string& x, const std::string& y, const std::string& z = "c"); // Error (2) // void concat(const std::string& x, const std::string& y, const std::string& z = "d"); // Error (2) // void concat(const std::string& x, const std::string& y = "b", const std::string& z = "d"); // Error (2) void concat(const std::string& x, const std::string& y = "b", const std::string& z); // a default for y concat("a", "c"); // (1) concat("a"); // (1) } // Function definition void concat(const string& x, const string& y, const string& z){ std::cout << x + y + z << '\n'; } int main() { func("a", "b", "c"); }

You can study the program on the Compiler Explorer.

::Casting away const from a const created object and try to modify it is undefined behavior: https://godbolt.org/z/YMn9jbdc7.

#include <iostream> int main() { int nonConstInt = 10; int* pToNonConstInt = &nonConstInt; *pToNonConstInt = 12; std::cout << nonConstInt << '\n'; const int constInt = 10; const int* pToConstInt = &constInt; int* pToInt = const_cast<int*>(pToConstInt); *pToInt = 12; // undefined behavior std::cout << constInt << '\n'; }

The modification of pToInt has no effect.

I suggest the following. Make all non-const member functions const. Duplicate the member functions that must also be non-const, and let the non-const version invoke the const versions. Therefore, you avoid code duplication and undefined behavior.

The first version of this idea is based on C++98, the second version on C++17:

- C++98

#include <iostream> struct C { const int& get() const { return c; } int& get() { return const_cast<int &>(static_cast<const C &>(*this).get()); } int c{5}; }; int main() { C c; const C c2; c.get(); c2.get(); }

- C++17:

#include <iostream> #include <utility> struct C { const int& get() const { return c; } int& get() { return const_cast<int&>(std::as_const(*this).get()); } int c{5}; }; int main() { C c; const C c2; c.get(); c2.get(); }

- std::ios::eofbit

-

AuthorPosts